Tod Brilliant leads the way down the stairs and across a dark basement to a refrigerator. He opens the fridge door as if opening a treasure vault. “This is what’s left for me,” the 36-year-old photographer says, motioning to the colorful boxes crammed inside. “When it’s gone, it’s gone.”

Brilliant, a Polaroid enthusiast, is showing his hidden stockpile of Polaroid film.

In an announcement last month that has many photographers in a frenzied scramble, the Polaroid Corporation declared that it will discontinue manufacture of its instant film by 2009. What may seem a natural demise to most—digital cameras having long ago surpassed Polaroids in sales and convenience—is an unrecoverable blow to a thriving subculture of photographic artists like Brilliant. His current show, “The End of Polaroid” at Ray Modern’s Micro Gallery in Santa Rosa, is designed as a “wake” for the forgotten yet beloved film.

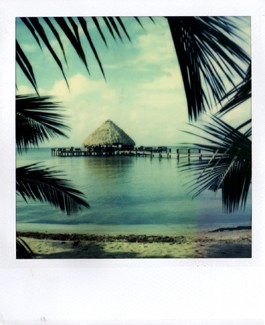

Sitting in a chair in Brilliant’s dining room, looking up at a 12-by-8-foot wall completely plastered with hundreds of Polaroids he’s taken over the years, one is immersed in the full sensation of a medium that defined America for the better part of a half-century. On the wall are images of old hotel signs, children wading in a pool, vacationers sunbathing on the beach, the Watts Towers, old cars. The shots appear to be from the 1960s or maybe the 1970s, but in a testament to Polaroid’s timelessness, Brilliant assures that they’re all from just the last seven years.

Despite the unique composition and color range Polaroids offer, Brilliant says, “I think serious photographers, by and large, look at Polaroid photography now as the retarded stepdaughter. A lot of people think of it as iconoclastic. But that’s not the reason why I like it; I just like the way it looks. You also don’t get to do it over. There are no second chances. I don’t have any problem with digital cameras at all, but with a Polaroid, you have to frame it and light it, and you have to get it right in the camera.”

Brilliant has a collection of about three dozen Polaroid cameras on display in his entryway, but he prefers the Polaroid 680, a variation of the popular SX-70 which takes film that’s still—for a few more months at least—available. He condemns the novelty cameras Polaroid made in the ’80s and ’90s after founder Edwin Land left the company. “That was kind of the end of Polaroid, just the really low-quality, mass-marketed plastic boxes that, you know, the hipsters still like, but they don’t take good pictures. And if your business is making cameras and your cameras don’t take good pictures, it’s only a matter of time.”

Polaroid introduced its first instant camera, the Land Camera Model 95, in 1948. No one had seen anything like it, and over the years Polaroid watched its stature grow. The company employed 21,000 workers in 1978, and in 1991, the company’s revenue peaked at almost $3 billion. Despite introducing one of the first digital cameras in 1996, the company was slow to embrace the future, and the digital revolution delivered a knockout punch to Polaroid. Last month’s announcement to discontinue instant film will leave the company with just 150 employees.

In essence, Polaroid died when the company filed bankruptcy in 2001. Most of the company’s business, including the Polaroid name, was sold to Bank One, whose OEP Imaging Corporation swiftly took on the recognizable title “Polaroid Corporation.” Then in 2005, that company was swallowed by Petters Group Worldwide, a holding company known for buying up failed brands with recognizable names. (Petters currently owns more than 60 such brands, and rumors persist that Petters decided to kill instant film right then, without telling anyone, while still selling instant cameras.)

The “old” Polaroid company, which actually remains in existence under Chapter 11 protection, has no assets, no commercial business and no employees. On paper, it’s known as Primary PDC Inc. It is, as the saying goes, an administrative shell, empty and lifeless.

Despite its vacation-snapshot association, Polaroid always attracted artists. The company hired Ansel Adams as a consultant in 1948, and a running stream of well-knowns have embraced the medium since, from Andy Warhol and Robert Mapplethorpe to William Wegman.

Chuck Close, the 67-year-old painter and photographer who has had a long, intertwined relationship with Polaroid, was quoted in the May 4 issue of New York magazine about the death of Polaroid film. “It’s not replaceable,” he said, “and they’re leaving it like roadkill. These corporate raiders who buy a company and strip it for everything profitable—they just pick the bones.”

Mike Slack is a 37-year-old Los Angeles&–based photographer whose Polaroid images have graced the New York Times op-ed page, album jackets by the British band New Order, numerous books and magazines, and have been collected in two acclaimed volumes, Scorpio and OK OK OK. For the last 10 years, he has worked exclusively with Polaroid; in his lifetime, he’s only spent about four hours in a darkroom. Slack’s preferred camera is the 680 SLR, a variant of the SX-70 that uses 600 film.

“The Polaroid is one of those inventions that to this day still feels both primitive and futuristic, like a light saber,” Slack says. “The pictures become physical artifacts the moment they’re made, and that moment of mysterious, chemical self-development is, literally, bound up in the very experience of looking through the lens and pushing the button. It’s all very physical and human and personal. There are all kinds of existential and spiritual metaphors one can attach to the Polaroid.”

For Slack, the unpredictability of a Polaroid is almost an artistic tool in itself. One day, while driving on I-10 through the California desert, Slack shot a photo through the window of his car, and his Polaroid 680 auto-focused on the glass instead of the landscape. “I inadvertently ended up with what looked like a tiny impressionist painting, dreamy and bright and strange,” he says. “After that, I found myself looking for ways to make Polaroids that seemed more like paintings than like photographs.”

Slack was not at all surprised when he heard that Polaroid would be discontinuing manufacture of its film, and remains stoic about the blow. Nevertheless, he’s officially going to have to find something else to do after the extended funeral season is over. “Like many other people out there,” he says, “I’ll buy a shitload of film, keep it in the fridge, make the best of it. I’ve had plans for a while now to make a third and final Polaroid book, if for no other reason than to have completed a trilogy, which has a good sense of closure.”

Slack has never had any direct relations with Polaroid as a company, but like others whose hearts are drawn to the medium, he’s frustrated at the way things have worked out. “As a company, Polaroid hasn’t been particularly imaginative, progressive, innovative or visionary in a long time,” he says. “All their best inventions grew out of a culture and economy of an increasingly distant past.”

Mark Aver, a graphic designer who was hired as a design consultant for Polaroid in 2003, knows the stuck-in-the-past atmosphere surrounding the “quiet and sleepy” Polaroid building in Waltham, Mass., firsthand. “They were weird, man,” Aver says. “I have yet to work for a client that is as weird as Polaroid.

“At their headquarters, you felt like you were stepping back in time 50 years,” he explains. “It felt like Houston NASA, 1952. Dudes walking around in stay-press pants and pocket protectors and really thick glasses, and everything’s beige and brown—it was like a dusty laboratory. So it was kind of cool in that regard, but then you’d leave thinking, ‘God, if they could just step into this century and revitalize themselves somehow.'”

At the time, Aver was involved with a top-secret project that the company hoped would resuscitate its standing once unveiled: an instant thermal-paper photo printer using no ink. After pitches for partnerships with Fuji and Samsung failed, the division split off into its own company, called Zink, which subsequently partnered back with Polaroid for name recognition. Currently, the small, handheld Zink printer, which produces 2-by-3-inch photos in 30 seconds from files on computers and cell phones, is Polaroid’s great push toward relevance. It will be unveiled in the fall.

During the interim between bankruptcy and the Petters takeover, Aver says the company was cripplingly divided on the issue of digital photography. He notes the company’s long-standing rainbow logo was changed to intentionally look more like pixels, reflecting a modern vision, but that the dueling sides couldn’t come together on the same wavelength, and employees seemed to be “going through the motions.”

“It just makes me sad even talking about them,” Aver says now. “Even in their halls, they’d have little exhibits of people who only shot Polaroid film, and they still did limited-edition art books. So someone there still cared about things. They just seemed unfocused.”

Polaroid has put out a call to other film companies, hoping that one of them will want to continue manufacturing the film, but everyone close to the cause seems to think that, at this point, it’s a hopeless case. The enormous investment required to recreate Polaroid’s film factories; the limited market it would serve; the cost and toxicity of the chemicals involved; and the fact that Fuji, an early contender for picking up the manufacture, already makes an instant camera which uses different film and would therefore be competing against itself should it take over, all makes the outlook bleak.

On a wooden support beam in Tod Brilliant’s living room, adhesive vinyl letters spell out the phrase “Beauty is found in the unraveling of things.” But in the unraveling of Brilliant’s preferred medium, there’s no beauty, only ache. When his stockpiled refrigerator supply of film is gone, Brilliant, along with all the other photographers, dentists, wardrobe departments, doctors, insurance companies and fashion designers who still use Polaroids, will have to move on.

In the meantime, Brilliant will walk around with his trusty Polaroid 680, taking photos, cherishing each one. One of his favorite pastimes is talking with complete strangers about the old-fashioned-looking thing around his neck. “You see kids in the park,” he says, “and you take a picture of them, and you give it to them, and their parents are always so excited.

“‘You know what this is?’ they say. ‘This is a Polaroid.'”

Tod Brilliant’s ‘The End of Polaroid’ exhibit shows at the Micro Gallery at Ray Modern through June 14. 606 Wilson St., Santa Rosa. 707.570.0128.

Museums and gallery notes.

Reviews of new book releases.

Reviews and previews of new plays, operas and symphony performances.

Reviews and previews of new dance performances and events.