Santa Rosa Stew

Janet Orsi

‘I don’t know who could be more sensitive to downtown businesses than I am. We listen, we hear, we are being as responsive as we possibly can.’

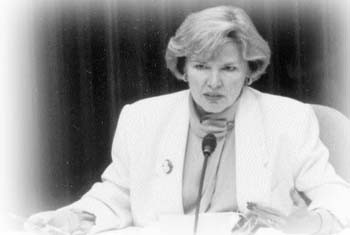

—Santa Rosa Mayor, Sharon Wright

Are too many cooks spoiling the recipe to save Sonoma County’s biggest downtown?

By Janet Wells

AT FIRST glance, downtown Santa Rosa seems like a pleasant place to spend some time and money. Stores, restaurants, fountains, crosswalks of tidy paving stones, benches, places to get stuff copied, lots of caffeine outlets. But stay awhile and try to catch the gotta-be-here buzz. Good luck.

At times, downtown appears to have a palpable anxiety that drives people away.

The twinkly lights along Fourth Street are festive at night–and cast a symbolic shadow on the unlit neighboring streets. During the day, restaurants are lively and crowded, offering an uncomfortable counterpoint to the plethora of empty storefronts. Railroad Square–the old part of town–has historic buildings, a renovated rail depot, and a pretty green slice of park that causes a lot of handwringing since it’s the preferred hangout for the homeless.

In the summertime, the Thursday Night Market attracts a big crowd to Fourth Street, although that hasn’t crossed over to the other six nights and three seasons. Groups of youth congregating around nearby Courthouse Square–unswayed by the classical music booming from the treetops, part of the city’s plan to discourage loitering–find downtown sidewalks perfect for lively socializing, driving lone pedestrians to the other side of the street.

Years ago, the city spent millions to split the square into two spiffy parks. Now the most populous element in the grassy areas are the signs prohibiting just about everything.

Everyone agrees that Santa Rosa, the county’s largest city, has the makings of a great downtown. So why all the long faces? Countless individuals, civic groups, business organizations, and city committees over the years have tried to push downtown to the pinnacle of its supposed potential. The result? A spruced-up commercial zone without a heart.

Santa Rosa’s downtown–bordered by Railroad Square on the west, Sonoma Avenue on the south, College Avenue on the north, and Brookwood Avenue on the east–is bizarrely bisected by Highway 101, one of the busiest freeways in the state, and Santa Rosa Plaza, an imposing shopping mall that sprawls over five city blocks. And just a mile to the south lies the bustling Marketplace, a year-old mall that gave many downtown shop owners the fits.

Now downtown has a 12 percent vacancy rate for both office and retail properties–down from an estimated 25 percent last year, but still more than twice the rate considered healthy. Those numbers aren’t the worst ever, but they’re far from rosy. Palo Alto, by comparison, hasn’t had over a 2 percent vacancy rate in its downtown for more than 10 years.

But what does a downtown really matter, anyway? If the market dictates that stores go out of business, so be it, right? People have plenty of alternatives in Santa Rosa for playing, shopping, and working.

Consider first, though, the sobering fact that sales tax revenue is Santa Rosa’s biggest single source of income, comprising 32 percent of the city’s $62.4 million general fund. Last year, downtown businesses, including Santa Rosa Plaza, contributed almost $2 million of that sales tax chunk to city coffers. Then consider that a downtown is a barometer for the rest of the city.

“Downtown is something that every resident of Santa Rosa should be concerned about,” says Santa Rosa City Councilwoman Noreen Evans. “Downtown is the heart and center of our city. It represents the character of our city. What’s happening downtown has an effect on the city, economically, socially, and culturally.”

Many voices contribute to the cacophony of opinion concerning downtown’s future. What will it take for downtown to thrive? Easier parking? More boutiques, movie theaters, night clubs, and restaurants? Better architecture? More office workers? Business tax incentives? Zoning changes? An arts center? Sidewalk cafes?

Maybe all of the above. It mostly boils down to–surprise, surprise–money and politics. Some people have high hopes for the city’s recently appointed Downtown Partnership Commission. Others say the commission is a city mouthpiece comprised of the same old political cronies. And with recently voter-approved urban growth boundaries curbing outward expansion, greenbelt advocates say this is the perfect time to boost downtown foot traffic and shopping with pedestrian-friendly planning and low- and middle-income apartments over storefronts.

Indeed, one wild card in turning downtown Santa Rosa into the county’s crown jewel could be titled “How Badly Do You Want It and Why?” Many downtowns boasting successful revitalization have had a cadre of people at the helm, people with not just a financial or political interest in such a project, but a personal stake in helping effect a civic transformation. However, Santa Rosa may have too many cooks in the kitchen.

When it comes to downtown revitalization, the city does not lack for people with ideas, passion, and commitment, but will they ever be able to agree on a recipe for success?

The City Official

Novice Councilwoman Evans made downtown the centerpiece of her November election campaign. An attorney who works downtown and is a regular at the local shops and cafes, Evans says she wants to help create “a place where people say, ‘That’s my town. This is where I go to hear music. This is where I go to hang out and buy my fresh produce on the weekend.'”

That warm fuzzy notion is far removed from the present. In one recent count of six square blocks of the downtown’s core, there were 19 empty storefronts. Check out the dearth of people on the streets–particularly at night and on weekends–and the picture is even bleaker.

“Downtown is in a really sensitive state of flux. . . . The market is de-emphasizing retail,” says Evans. “Downtown can go in one of two ways. We can put in the time and effort to fill up storefronts or continue seeing decline and decay.”

Evans is acutely aware of the politics involved in such an endeavor. She was appointed to the Planning Commission in 1993, when the city was in the midst of a major brouhaha over the proposed Marketplace, which boasts big-draw discount stores like Costco, Target, and Office Depot.

Greg Rogers, Santa Rosa’s financial planning manager, insists that, despite dire predictions, downtown businesses have not suffered because of the Marketplace, which provided “pure straight growth” and added more than the $500,000 in sales tax revenue last year to the city’s coffers.

Ask any downtown merchant about the Marketplace and they won’t jump for joy.

Evans considers it a tradeoff, at best. “It did bring new jobs, retail, and tax dollars. But it is not without negative impacts on downtown,” she says.

Consider these figures: Last year, total taxable sales at the Plaza reached $190 million; downtown businesses rang up $45 million in 1996; and in just one quarter, from May to August, the Marketplace racked up a hefty $35 million in sales.

Evans doesn’t believe that the Marketplace takes business directly away from downtown merchants, though it certainly doesn’t help fill those empty stores. After all, a single, small downtown business probably isn’t going to attract much enthusiasm from city hall as a candidate for fee waivers or other incentives.

“It takes a city that’s willing to say no to certain types of development in certain places and areas,” Evans says, “and that hasn’t happened.”

Is the City Council ready to do that now? “I don’t know,” she adds.

For now, Evans is focused on a downtown project that’s less politically charged than big-money development decisions: Santa Rosa Creek restoration. “That creek goes right under city hall,” she observes. “There used to be good steelhead fishing in Santa Rosa, and there’s a fish ladder under city hall. We’ve had this crazy idea to tear up city hall and get the creek back to the light.”

While that plan is a little extreme, there is a $5.6 million pot from the city’s redevelopment agency and the Prince Family Trust to create a pedestrian/bicycle path along the creek and restore the creek’s natural ecosystem between Santa Rosa Avenue and Railroad Avenue, site of a planned convention center.

But creek restoration is just the beginning of Evans’ enthusiasm for revamping downtown. “Have you talked to anyone about all the other stuff going on? Trains stopping at Railroad Square? The convention center? A multiscreen theater? Reuniting Courthouse Square?” she asks. Downtown needs projects like these, she insists, along with cultural activities, affordable housing, and restaurants to attract “people on the street 24 hours a day with money in their pockets ready to spend.”

The Merchant

Downtown stationer Dave Madigan likes to call himself a troublemaker. He certainly minces no words in assigning blame for downtown’s woes. “I blame [Mayor] Sharon Wright,” he says bluntly. “I don’t think she has the downtown’s interest at heart. I think taking care of her political friends and allies has been her No. 1 goal.”

Wright–who works for the Chamber of Commerce, consults for the building trade-oriented Sonoma County Alliance, and chaired the former Downtown Development Association for seven years–is baffled at the idea that she doesn’t fairly represent the downtown community. “I’ve been in business or had an office in downtown since 1981. I don’t know who could be more sensitive to downtown businesses than I am,” she says. “We listen, we hear, we are being as responsive as we possibly can.”

Madigan doesn’t buy it. “I’ve taken a lot of flak for blaming bad changes on the city itself, on the City Council. They haven’t cared. Their only interest is in tax money. I’ve tried to work with the City Council over the years and nothing ever happens.”

The Madigan family stationery store at Fifth Street and Mendocino Avenue has been a downtown fixture for 41 years. And 35-year-old Madigan grew up downtown. “I’ve been here since I was small enough that the cash register used to hit me in the head when it opened,” he laughs.

Madigan doesn’t do much business with the city–“I had someone buy forms the other day, the first time I’ve had [a city staffer] in this store in 10 years”–and has been unimpressed with the city’s attempts to turn downtown into a showpiece. The city renovated Fourth Street a few years ago, “but forgot about Fifth Street, Third Street, Mendocino Avenue,” he says.

Last summer, Madigan organized the Downtown Business Association, a group of unaffiliated merchants, after feeling frustrated by the myriad official committees that have been formed downtown. And don’t confuse Madigan’s group with the Downtown Partnership Commission, a 17-member group appointed by the City Council in December and the latest downtown organization to incur Madigan’s ire.

“We have too many of the people [in these groups] being reused over and over, favorites of the City Council,” Madigan says. “The city set up that group so it wouldn’t have to deal with groups like mine. The Downtown Partnership Commission won’t rock the boat. They will rubber-stamp whatever the city wants.”

What is it that Madigan wants and feels he isn’t getting? Parking.

“A parking ticket fee is $15 for an expired meter or $20 on Fourth Street for going over the time limit. That’s outrageous when I can go to Coddingtown or the Plaza and park free all day,” he fumes. “If you come downtown for a $3 sandwich and get slapped with a parking ticket, where are customers going to go [in the future]?”

Parking in downtown Santa Rosa is a dream compared to downtown parking in many cities. Santa Rosa’s five city garages–with 3,000 spaces–allow 90 minutes of free parking, and many of the 1,175 street meters take nickels and dimes as well as quarters. Some lots even allow 10-hour parking. Try to find that in San Francisco.

Still, most communities in the county offer limited, free downtown parking, while Santa Rosa garners more in parking fees than tax revenue from its downtown. Revenue from city garages, meters, and permits was $1.6 million last year, along with an additional $712,000 in parking citations. By comparison, retail tax revenue from downtown businesses (not including Santa Rosa Plaza) was about $453,000 during that period.

So which is more of a priority to the city? “If [Santa Rosa’s city parking and transit management officials] think they can get away with it, they will write everybody’s grandmother a parking ticket,” Madigan answers.

One of Madigan’s first goals for the Downtown Business Association was to have parking meters removed. The city nixed that idea, so now he’d like to see a “kinder, gentler ticket policy,” with $10 as the maximum citation.

In October, the DBA surveyed 600 downtown businesses and merchants and found that most want cheaper parking for customers, an 11 p.m. curfew for teens, and fee waivers for major projects. Another key goal of Madigan’s group is to avoid having to pay any kind of mandatory fees or assessments to be part of a downtown group. All downtown merchants used to pay up to $2,000 to the Downtown Development Association for parking assessment, promotions, and security. That group disbanded in 1993 in disarray after local businesses complained that they weren’t getting enough for their money.

Madigan is wary that the Downtown Partnership Commission will resurrect mandatory fees for group marketing and promotions. “I know how to do that for my business. Why should I pay someone else?” Madigan asks. “If [the Downtown Partnership Commission] tries to shove it down our throats, we’ll just give them the finger.”

The Commission Member

Santa Rosa Plaza manager Chris Facas has been on a lot of downtown committees. By his admission, most have failed to accomplish much. “There were a lot of incarnations of groups, all with good intentions, none of which were ever recognized by the city,” Facas says. “You can do some projects, but you can’t get a good comprehensive outlook unless you have the city’s involvement.”

Facas has just been chosen head of the new Downtown Partnership Commission, which, he ways, “truly represents downtown.” There are a number of people who would argue with Facas about who exactly represents whom, but the commission certainly has some heavy hitters on it, including Mayor Wright, Councilwoman Evans, and San Francisco developer Tom Robertson, who has an ownership interest in about 85,000 square feet of downtown property, including the refurbished Rosenberg Building that houses Barnes & Noble Bookstore.

The group’s mission is to carry out recommendations from previous downtown studies. While the commission faces all-too-familiar issues, the intent this time is different, assures Facas. “The furthest thing from anyone’s mind is to come forth with another plan or another document,” he says. “This group’s function is to make real change, to make these things happen.”

Facas would like to see the downtown area become “the cultural mecca of the county.” That goal is shared by Robertson, whose San Francisco North Properties owns a partnership in the Fifth Street building that houses the Sonoma County Repertory Theatre and Massés Billiards.

Robertson, widely regarded as the single most influential person in the future of the downtown and a proponent of a strong downtown cultural element, declined to be interviewed in depth for this story. He has said in the past, however, that he considers downtown Santa Rosa to be an undervalued gem.

“The downtown is vibrant, but not anywhere near where it could be,” Facas says. “That means the incentives aren’t out there for it to happen.” Facas sees an incentive program, such as fee waivers or zoning restrictions, as a crucial step in encouraging businesses to locate downtown.

Facas also believes it is time to revisit the idea of a local merchants’ association. “Marketing the center [of the city] and themselves and events is what makes people come out,” he says. “Money for that will have to come from the downtown merchants.”

That news should send Madigan’s blood pressure soaring.

Facas is in an interesting position as a commission member who also happens to manage a shopping mall that not only creates a barrier between downtown’s two sections, but also competes with downtown businesses. The relationship between the mall and downtown businesses certainly isn’t synergistic, although that’s the ultimate goal. The elephantine Plaza, with free parking for 3,200 cars and a byzantine maze of entrances and exits, creates a barrier to through traffic.

Optimists who see the Plaza as a link between downtown and Railroad Square have never tried to get from one to the other after the mall closed. The Plaza, opened in 1980, hulks over Third Street–the only walkway between the two sections of downtown–creating a subterranean pathway that is dank, dark, and scary. Meanwhile, ideas such as lighting, murals, signage, and sidewalk handrails to encourage (not to mention protect) pedestrians have yet to be implemented, and even a low-cost trolley bus that transits the two areas goes largely unused.

“I probably have less to gain, from a business angle, from a vibrant downtown than downtown businesses do,” says Facas. “But I come here every day. I virtually live in the downtown area. That’s the main reason to be involved. I see the potential it has.”

Janet Orsi

‘The city’s vitality–Sonoma County’s vitality to a large extent–is dependent upon downtown. Those businesses that move in and don’t find a niche don’t survive. You have enough failures in an area over time and it gets a bad reputation.’

—Bob Marshall

The Gadfly

When Bob Marshall retired, he and his wife wanted to move to a small apartment in downtown Santa Rosa. “I wanted an urban environment where we could have one car between us and I could walk out in the morning to buy coffee and a bagel.”

The search for housing didn’t turn up anything affordable, but it did pique his interest in downtown revitalization. “I go to all the meetings. I’m a gadfly,” says the genial Marshall. “I’ve done a ton of reading over the years.”

Marshall agrees with urban theorists Jane Jacobs and Lewis Mumford and their criticisms of 1950s and 1960s downtown planning as being people-unfriendly. “It’s impossible to walk across the street. That’s really where we went wrong with downtown,” he says. “The freeway bisects it. There’s a mall plunked down in the middle.”

For Marshall, the building vacancies and lack of foot traffic are downtown’s biggest detractors. “[Courthouse] Square is very underutilized,” he says. “It should be the center of our town, a place to sit if there’s an art fair or a concert in the afternoon. As it is, the noise of the tires going by on the cobblestones, bumpity-bumpity-bump, even throws the musicians off. The center court in the shopping mall is replacing the town center.

“The city’s vitality–Sonoma County’s vitality to a large extent–is dependent upon downtown,” he continues. “Those businesses that move in and don’t find a niche don’t survive. You have enough failures in an area over time and it gets a bad reputation.”

But downtown isn’t a lost cause, adds Marshall. “The old hulk of a Rosenberg department store that once represented urban blight is now refurbished and one of the good places downtown.”

With corporate giant Barnes & Noble taking over the Rosenberg Building at Fourth and D streets, downtown now has three major bookstores in close proximity. Instead of taking business from the smaller, independently owned bookstores, Marshall believes, Barnes & Noble has increased the customer base of its competition.

“These stores attract a good cross section of people, and support a couple of good coffee shops, too,” he says. “Those three stores, plus the record shops, are not competitive with suburban malls. Crown Superstore [a chain retail book seller] is starving in the Marketplace, [as far as I can see]. You can roll a bowling ball down those aisles.”

People go to the Marketplace not for a shopping experience or leisure, but to buy. And buy they do in record amounts for Santa Rosa. Marshall suggests that those tax revenues from the Marketplace that exceed original estimates be used as incentive subsidies for turning downtown into a niche of hospitality and entertainment.

“Let’s enjoy the revenues and use some as seed money to relocate certain businesses downtown,” he says. “That will bring a lot of people.”

The Urban Designer

Laura Hall doesn’t live or work downtown. But that’s where her heart is. “I studied public open spaces in school. I love talking about plazas,” says the urban designer with Carlile, Macy, Mitchell & Heryford.

Hall is a member of the Coalition to Restore Courthouse Square, a group that is working to redesign the old square–split in two in the late ’60s–and block the cobblestoned stretch of Santa Rosa Avenue that runs through the middle. “Santa Rosa is in dire need of having a heart that is not bisected,” Hall says. “Twenty years ago we started carving up downtowns for cars. That was the model of the time. Everyone did it all over the country.

“People don’t want to admit that they made a big mistake by bisecting the square,” she adds. “A lot of money went into the design and existing configuration of the square, and it’s really easy to get defensive when you’ve spent a lot of money.”

Downtown’s real foe isn’t parking or competition from malls or even vacancies, she continues. Those are just symptoms of downtown design that, in places, goes “way beyond pedestrian-unfriendly to pedestrian-terrifying.”

“It’s about architecture and whether buildings work, about spaces divided up correctly to invite pedestrians,” she says. “People are fooling themselves if they think downtown will work with Courthouse Square the way it is. It’s two big dead spaces. It draws energy out.”

The coalition’s report on reunification design, cost estimates, and traffic impacts is due in March. Preliminary estimates put the project cost at about $1.8 million, says coalition chair Terry Price. He emphasizes that the group plans to fund the project with private sources and public grants, rather than any kind of tax assessment for downtown businesses.

He adds that preliminary traffic studies show that the impact of blocking Santa Rosa Avenue, one of the busiest arteries through downtown, is significantly less than many business owners fear. “The amount of time increase we’re talking about at an intersection is a matter of seconds, ” Price says, adding that some slowdown in traffic is desirable. “We want downtown to be a place people go to, not speed through.”

Right now, groups of kids are about the only people hanging out in Courthouse Square and on downtown sidewalks, a trend some shoppers and merchants find disconcerting. “A lot of people find it hard to walk in front of 30 young people. They don’t like to feel that conspicuous. But it’s easy to use kids as scapegoats,” says Hall. “When any one group takes over a spot, there’s something wrong with it.

“You want a cross section.”

Courthouse Square, which has “no clear path of navigation,” makes people feel uncomfortable, she adds. The coalition’s design calls for a more traditional town square, tree-lined, with diagonal walkways. “The square won’t solve all the problems, but it will be an opportunity for pedestrians, for more people on foot,” she says. “People are yearning for these kinds of spaces.”

Downtown itself is a business, and “businesses tend to have a life cycle of about 50 years,” says Santa Rosa Economic Development Specialist Lyn DeLeau. “Our downtown has lasted 150 years, and the reason it has–not to put too much of a Pollyanish spin on it–is because people are looking at it again and again, keeping up with a changing economy and competition.”

The problem now, she says, is the lack of a “unified voice of downtown [merchants and residents] to come to the council and say, ‘These are the kinds of things we need.'”

Clearly, downtown revitalization is a quagmire of ideas, opinions, criticisms, and emotions. But common themes do emerge. One refrain? Every person interviewed for this story interrupted their litany of downtown ills to point out that Santa Rosa has a good downtown. Such a statement can sound plaintive, defensive, and well, lame, in light of the statistics and the lack of bustle on the streets.

But for the optimist, perhaps it’s a rallying cry, the starting point of consensus, and a long-awaited sign that all these chefs just might succeed in coming together to cook up a great downtown.

From the February 20-26, 1997 issue of the Sonoma County Independent

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

© 1997 Metrosa, Inc.