Great Divide

Michael Amsler

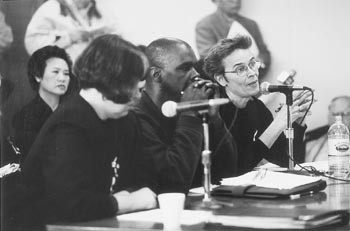

On the Agenda: Tanya Brannan of the Purple Berets, left, Steven Campbell of the Homeless Coalition, and Karen Saari of the October 22 Coalition testified before the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights last week about alleged police brutality.

Aftermath of civil rights hearing: Now what?

By Paula Harris

WHILE the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report on alleged local police brutality isn’t due for six months, some who attended a daylong hearing last week that underscored the division between police and social justice advocates are working with renewed vigor to bridge the gap between the two sides.

“In order to move forward, we have to find some middle ground and begin hearing each other,” says Elizabeth Anderson, director of the Sonoma County Center for Peace and Justice. The center’s board of directors met Monday night and renewed their determination not only to advocate for civilian police review boards, but also to initiate discussions in each city about police-community relations. “We need to begin to identify what we can do.

“We’re on the right track–the community just needs to keep building on what’s been started.”

In the wake of last week’s civil rights hearing, which examined police policies and procedures that may have contributed to between eight and 11 police-involved deaths in the county in the past two years, issues now being explored include looking at how other communities have handled similar police-community relations issues, Anderson says. “We don’t need to reinvent the wheel,” she says, adding that if the county needs to bring in outside experts, it should do so. Also, she adds, local law-enforcement agencies could start additional cultural sensitivity training immediately, without waiting for the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report. “We don’t have to sit on our hands.”

Sonoma County Human Rights Commissioner June Moes is hopeful that better understanding can be achieved during an upcoming Human Rights Commission forum. The commissioners (six of whom attended the state and federal hearing) all agree that steps must be taken to mend the split between community members and law enforcement officials. “Obviously, we need dialogue, and my hope is that the commission can pick up the ball and run with it,” says Moes, stressing that the county commission is not anti-law enforcement. Of the 13 commission members, two are Santa Rosa police officers and another is a retired law-enforcement official.

Both Anderson and Judith Volkart of the American Civil Liberties Union of Sonoma County stress the need for local government to become more involved in the debate over police practices. The women had sent personal invitations to all city council members and Sonoma County supervisors to attend last week’s hearing. “The agenda now needs to be set by local communities,” says Volkart. “Each of the communities needs to begin looking at policies, procedures, and hiring practices of local law enforcement that will reflect community values while still preserving the safety of officers.”

MEANWHILE, Volkart is concerned by the tone of law enforcement officials–many of whom have complained that statements made to the panel were “distorted”–during and after the hearings, and worries that it may be tough to re-establish talks. “It sounds like they are locking the door and shutting us out,” she says. “They don’t seem eager or even willing to have discussions.

“But the best weapon police can have is their community’s confidence.”

Law enforcement officials contacted for this article did not return calls this week.

Others encourage the ongoing attempt to foster communication. Don Casimere, a former Berkeley police sergeant who for the past 14 years has worked on civilian police review for the Richmond Police Commission, believes “citizens can objectively and fairly impact police services.”

Casimere was part of a panel of police procedure experts who testified at the Feb. 20 civil rights hearing.

This week, Casimere said both law enforcement officials and the community have work to do in building better understanding between local police and community members and overcoming barriers to communication to restore confidence and improve relationships between the various factions.

“There needs to be further dialogue,” he says. “It doesn’t need to stop because the commission is no longer in town.”

City and county government should take some responsibility for further talks, he adds, so that not all the burden falls on community groups.

“It’s not police against the community or the community against the police. I’d think enlightened police executives would welcome citizens’ advice on community matters and not be intimidated or angered by input,” Casimere says. “It doesn’t have to be either hard-nose enforcement or community policing. Police are charged with enforcing laws, but there has to be a balance, with police officers providing services to the public that people are entitled to.

“We’re talking about bringing the ‘them’ and ‘us’ together to make ‘we’–a community.”

ALL IN ALL, committee members were perplexed by the tenseness in the room and the level of hostility and outrage in Sonoma County. “I’ve never seen such an intensity of interest and a ‘them’ and ‘us’ attitude,” said U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Vice Co-Chair Cruz Reynoso, a former California Supreme Court justice.

He scanned the packed room and pointed to the symbolic yellow badges worn by some as an example of the divisiveness.

“There’s something here not completely healthy.”

During their presentation, Police Chiefs Mike Dunbaugh and Patrick Rooney and Sheriff Jim Piccinini reeled off lengthy lists of their departments’ accomplishments.

“Congratulations on the public service activities, but the reason we’re here today is to discuss policies and procedures,” State Civil Rights Advisory Committee member Dena Spanos-Hawkey reminded them. “I live in Los Angeles and when you top us that’s pretty incredible.”

However, Piccinini said the committee was “being misled by specialinterest groups.” Not so, said Volkart. “It’s not a few fringe elements and activists,” she told the civil rights panel, adding that some factions who are concerned that police seem to be refusing to give up investigative control to the community are not “anti-law enforcement.”

From the February 26-March 4, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.