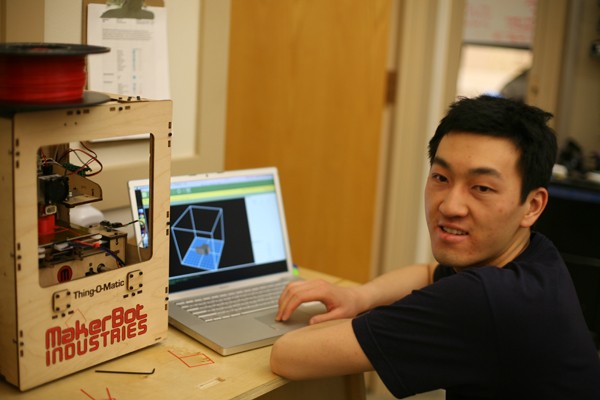

Eric Chu is a 23-year-old intern at Make magazine’s Make Lab in Sebastopol, and he’s seen the popularity of 3-D printing first-hand. While working Make‘s 3-D Printing booth at the Maker Faire in San Mateo last month, Chu sold over 20 Thing-o-Matic printers—at $1,750–$2,000 each. Just as dot-matrix and then ink-jet printers dropped in price, so too have 3-D printers. There are models for around $500, and, says Chu, “I wouldn’t be surprised if there was one for $200, or even $100, in a year or so.”

On a recent Friday night, Chu and his fellow intern Max Eliaser work late in the Make Lab testing projects for Make, utilizing a 3-D-printed component for a levitating motor. Around the cluttered testing area, other 3-D-printed items abound from the three different printers—a Thing-o-Matic, an Up! and an Ultimaker—in use at the Make Lab: a spindle for the ABS spool; a half-printed bust of a man; various caps and parts for projects. There’s even a yo-yo that Chu, who grew up in Cloverdale, has printed out, and he whips it around his wrists just like a Duncan Butterfly you’d buy off the shelf.

Any concerns about how precise 3-D printing might be are laid to rest when Chu demonstrates printing out a basic sports whistle, complete with a ball inside. The MakerBot whirrs and beeps and bloops (“It sounds like a Tron movie,” Eliaser quips), and 39 minutes later Chu picks up the red plastic whistle, dislodges the ball and blows a loud bleat. Unless you’re looking at it up close, it’s virtually impossible to distinguish the printed version from a whistle one might buy at a store.

“The printer prints in layers, and you can actually reduce the layers to about four microns, from what I’ve heard,” explains Chu, likening the process to the dpi resolution of a jpeg. “The thinner your layers are, the higher the resolution your part has. So say you have a curve, or a sphere, if you have really thick layers, you’ll be able to see all those lines. It’s not going to be perfectly smooth to the touch. But at four microns, it’s really hard to see those lines, and it’s nice and smooth.”

Chu’s preferred site for 3-D printing plans is Thingiverse, which has a system set up to accommodate different types of licenses. Many of them, Chu notes, are Creative Commons licenses. “This whole 3-D-printing community is all about open-source,” he says. “It’s all about sharing the technology instead of keeping it locked down with patents.”

With 3-D printers potentially in homes nationwide, and with free licensing of plans, could a revolution in 3-D printing cause an upheaval in the manufacturing industry? Chu isn’t so sure, at least for the immediate future. “You can’t really have a super-high-end printer in your home and manufacture a few thousand parts easily at your home,” he says. “It’s definitely not that high-end. Yet.”